Jerry Remy talks of his depression after cancer

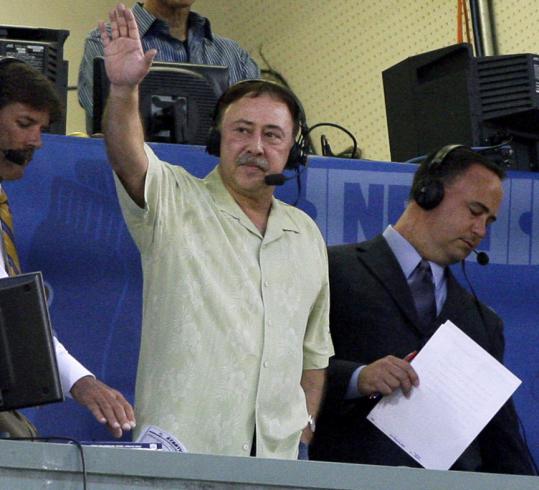

Jerry Remy says it is important to talk publicly about dealing with depression. (Elise Amendola/Associated press)

As cancer survivors, many of us have struggled with that unexpected feeling of depression and loneliness that surprises us after treatment is finished. I say unexpected and surprises, because for many of us we are quite often shocked and confused at the intensity of the feelings of depresssion that hit us. Surely we should be ecstatic – after all we have “beaten” cancer? We have been given a second chance, so why do we feel so sad?

The fact is that cancer survivors are more likely than their healthy peers to suffer serious psychological distress such as anxiety and depression, even a decade after treatment ends. The physical and emotional fallout of cancer treatment can contribute to feelings of anxiety and depression. This is a theme I return to time and again in this blog, but I feel it is important that we speak out about it, and it doesn’t become, like depression often does, a hidden grief in our lives. That is why I am so pleased when cancer survivors in the public eye speak out about their experiences with depression whether it is cancer related or not. It helps to remove some of the stigma.

Red Sox commentator, Jerry Remy has been speaking out this week about the wave of depression had swallowed him up in the months after lung cancer surgery. It is, according to a Boston Globe article, a story that rang with sad familiarity to psychologists like Karen Fasciano, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

There, she sees patients who are bereft and bewildered. During the months of chemotherapy and radiation, their lives had structure, support, and a singular, energizing focus: defeating cancer. But with treatment finished, some patients suddenly find themselves alone, exhausted, and fixated on how cancer has transformed their lives. And they are consumed by the potential that it could return.

“When you have cancer, often the most essential element is saving your life,’’ said Fasciano, who devotes a substantial amount of her time to helping patients who have finished cancer treatment. “But when people are done with their medical treatment, they experience the existential and emotional adjustment issues related to having had a life-threatening illness.

“Life is uncertain for all of us,’’ she said, “but people who’ve just gone through cancer treatment have a new awareness of that uncertainty.’’

On Wednesday night, from the familiar terrain of Fenway Park, Remy first spoke about his descent into depression. In a telephone interview last night, he described days and nights spent in a state of forlorn emptiness.

“You didn’t want to get out of bed,’’ Remy said, his voice strong, his words plainspoken. “The first thing you thought when you woke up was ‘another lousy day is ahead of me.’ I had no desire to do anything.’’

Mary K. Hughes, a clinical nurse specialist in the psychiatry department at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, said recent cancer survivors can easily become overwhelmed if they return to work and life’s other routines too soon.

“They can’t do what they used to do,’’ she said. “That starts them thinking: ‘What if this is forever? What if I’m never going to be able to work?’ And then all those fears start rising.’’

There’s debate among mental health specialists about just how many cancer patients and cancer survivors experience that crash.

Dr. William Pirl of the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center said doctors used to believe that up to 25 percent of cancer patients experienced major depressive disorder, the sort of depression that is far more than a passing bout of the blues. More recent reviews, he said, suggest that a truer figure is 10 percent.

Still, that rate fails to capture patients who have milder forms of the condition, particularly those stricken with something called an adjustment disorder. As the name implies, those patients experience transient depression as they adjust to being diagnosed with cancer.

Patients are also vulnerable to depression midway through treatment, when the deleterious effects of chemotherapy and radiation become more apparent, said Pirl, who studies the treatment of depression in lung cancer patients.

“They’re feeling poorly, and they don’t know whether the treatment is working or not,’’ said Pirl, clinical director of Mass. General’s psychiatric oncology service. “They’re left in this ambiguous zone of not knowing whether their investment is going to pay off and thinking that maybe they’re going through treatment for nothing.’’

There’s also reason to suspect that the powerful treatments used to vanquish cancer may light the fuse of depression, specialists said. The drugs can start a cascade of metabolic and hormonal changes and cause inflammation thought to contribute to the condition.

The Institute of Medicine, an independent body that advises Congress on health affairs, issued a report in 2007 calling on cancer specialists to do a better job recognizing the psychological impacts of the disease and its treatment. Pirl conducted a national survey of oncologists a few years back and found that only two-thirds asked patients how they were coping.

When depression is identified, doctors sometimes prescribe antidepressants and refer patients to counseling.

Remy said last night that his doctors have tweaked his medication so that “they’ve got me going on the right track.’’

Knowing that his absence from the broadcast booth would invite speculation, Remy said he felt it was important to talk about dealing with depression.

“I’m not embarrassed to say so,’’ Remy said. “People go through it all the time. It’s probably best to tell the truth, and that’s what I did. And if it helps people, that’s good, too.’’

This post adapted from the Boston Globe.

Related Posts:

The loneliness of the long-distance cancer survivor

Most people know so little about the major and life disrupting treatment that cancer patients have to endure…

Less is known of the psychological impact of treatment for cancer…

Glad that Remy felt able to talk about the depression he went through… this can only help others in the same situation, their family and friends and help to educate the public as a whole.

Good article…Thank you.

LikeLike

And thank you for your insightful comments too.

LikeLike

Pingback: Depression Awareness Week « Journeying Beyond Breast Cancer

Pingback: I’ve beaten cancer, so why am I still sad? « Journeying Beyond Breast Cancer